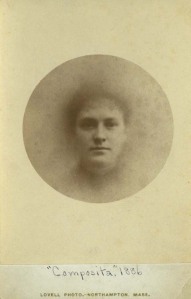

The Story of Composita Ocgenta-Sex

In the winter of 1885/1886 a group of Smith College women created a tangible symbol of their college friendship. The forty-nine members of the senior class had their individual photographs taken. The negatives from these images were then merged at a local photography studio to create a single composite portrait of the class. Given her own identity/name “Composita”, the Class of 1886 carried the image of this woman and “classmate” with them throughout their long and rich history, until the final member of the Class died in 1964. What is the story of Composita, and how does this single act of creating an individual identity from many tell us about friendship within the Class?

A Bonding We Will Go

The Class of 1886 entered Smith with 69 students. While they represented states as far away as Michigan, Maine, and New Jersey, the majority of students were from the New England region. By 1885, the beginning of their senior year, the total number had been reduced to 49. Throughout their four years together, the class found countless ways to express their solidarity and friendship.

Class meeting minutes provide evidence of the various ways they bonded. Beginning with their first class meeting in September issues of class identity were addressed. Discussions about the color of class sashes, the calophon of class stationary, and the design of their class pin lasted for several months. These manifestations of class identity were continually debated for a two-year period. While the color of a sash might seem like an unimportant issue to us today, for Smith women it was not. The official color of Smith is white, and each class is now assigned red, green, yellow, or blue as their class color. The early classes were responsible for deciding their own colors. This act of decision-making early in their career at Smith assisted with their formation of class-identity.

A strong, overall class identity was fostered also by self-governance. A president, vice-president, secretary and treasurer governed the class. Class meetings were held regularly throughout the year and attendance was always high. Throughout their four years, no single set of individuals moved to the forefront to become the core leaders of the class. Numerous opportunities were given to different class members to take leadership roles. Organizing extra-curricular entertainment took up a vast amount of their time. The class sponsored a series of teas and dances for the senior class, including an “English High Tea” for the seniors in 1884 where ushers and waiters were expected to dress up as Oxford students, ie., men. They organized sleigh rides and evening serenades with beloved professors, young and old. They debated the desire for a class pin, an official class photograph (not Composita), and subscriptions to regional and international newspapers. All of these activities provided ’86ers with the opportunity to work on committees and a vast majority of them chose to do so. When the class decided to have an official group portrait taken they invited ex-members of the class to join them in the photograph. If there had not been such solidarity for being a member of the class, why would the ex-members be invited to return?

Another way of defining their class identity came through the housing system at Smith. One of Smith’s unique aspects is its residential system of small houses instead of large dormitories to house students. This system grouped student houses around a large academic building. Each house had a separate dining room, parlor, kitchen, and “lady in charge” who was the social and moral arbiter of student life. In the promotional literature of the College, the system is described as a way for “young ladies [to] enjoy the quiet and comfort of a private home, and at the same time, the advantages of a great [literary] institution”. Such a setting would alleviate the fears of parents who had difficulty in sending their daughters away from home, and who were fearful that these young women would end up thinking more about careers than preparing for marriage. But the College did not want to encourage the development of house cliques, and so provided a large social hall in the academic building, for “the purpose of bringing together as often as may be deemed profitable, all members of the College and their friends, in social intercourse.”[1] Not only did the members of the Class of 1886 have opportunities within their own class to bond, but through major social events they regularly socialized with other Smith students. Yet the bond they shared among their class was especially strong and is seen most concretely in the composite class portrait the woman named “Composita.”

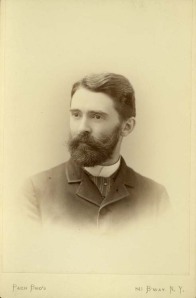

The man with the camera: John Tappan Stoddard

The first time Composita is mentioned is in the class meeting minutes of October 23, 1885. There is it noted that, “the question of the composite photograph was raised: it was stated that Hardie & Lovell [the local photographic studio] would take it at their own risk, and it was voted that we have it taken.”[2] The “risk” for Hardie & Lovell most likely refers to the fact that composite photography was still in its infancy during this period and did not become a popular form of photographic expression for the lay person until the early 1890s. Scientists argued in their journals that composite photography was best used as a tool for ethnographic work centering on the identification of racial and individual characteristics. Smith students would have been aware of this type of photographic work through their physics and chemistry courses.

The first composite portrait of Smith students was taken by John Tappan Stoddard, a professor of chemistry and physics at Smith College between 1878-1919. Stoddard, a handsome, native son of Northampton, was one of the students’ favorite professors. Whether teaching chemistry labs or playing tennis with undergraduates on the lawn in front of one of the student residences, Stoddard was a popular professor. A graduate of Amherst College, Stoddard went abroad to complete his graduate education, and returned from Germany to teach at Smith beginning in 1878. He was the author of many standard textbooks in the fields of general and organic chemistry. He was also an avid billiards player and wrote a popular book called the Science of Billiards with Practical Applications (1913). A true renaissance man, he was interested in science and literature, and found in photography a new teaching tool. He was one of the first faculty members on campus to use a camera to teach optics and refraction in his physics classes.

Like many of his day, Stoddard’s interest in photography merged with theories of identification and race into what today we call eugenics. In 1883, the scientist Francis Galton, published a volume titled Inquiries Into Human Faculty and Its Development; a compendium of articles he wrote about his work between 1878 and 1881 exploring the influences of heredity on the physical, spiritual and moral nature of man. In this volume, Galton discusses his use of composite photography as a tool to assist in identifying traits shared between family members, criminals, inmates of asylums, and members of different ethnic ‘racial’ groups. Galton also wrote an article published in Nature magazine about composite photographs that furthered his ideas about employing photographic evidence of ‘typical group’ portraits via composite photography. It is very likely that Stoddard read Galton’s work and became interested in composite photography through these publications. Stoddard wrote a number of articles about the use of composite photography for popular and scientific magazines, such as Science, and Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. A published image of Composita first appears in the July 1886 issue of Science. In this issue, Stoddard discusses the use of composite photography as a tool for locating the “pictorial averages of groups.” In his second article published in 1887 for Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, he discusses the process by which he created the composite photograph and the similarities and differences each image produced. Not only did he take the “Composita” portrait of the graduating seniors of the Class of 1886, but he also took images of members of his Physics class, and a sub-set of other classes, which he then made into composite images. Another interesting point is that while much scientific literature on composite photography focused on images of scientists, working class men, criminals, the insane, and soldiers, only Stoddard’s work appears to have an entirely female group as its focus.

While Stoddard ‘s interest in composite photography appears to be one of purely scientific interest he opened the door for members of the Class of 1886 to use it in a completely different way.

Composita Ocgenta Sex: the Play

The influence of Composita and photography with the Class of 1886 is manifested in a variety of ways. Copies of Composita are found in numerous photograph albums of the women, attesting to their desire to have this visual keepsake of their time at Smith. One extremely interesting appearance of Composita was as the lead character in the Class of ‘86’s senior class play: Composita Ocgenta Sex: A Drama In Three Acts by one of her Components. It was written by class member, Zulema A. Ruble who came to Northampton in 1880 to prepare at the Mary A. Burnham School, which stood directly across the street from Smith College. Her friendship with another future Class of 1886 member, Henrietta H. Seelye began there. In her tribute to Ruble in the 1934 necrology entry in the Smith Alumnae Quarterly, Seelye described her in this way:

“Her greatest interest in those two years [at the Burnham School] was the study of Greek with Miss Burnham. In College, Zulema continued her faithful work in the classical course and brought honor to Eighty-Six by writing for Senior Dramatics the play “Composita.” Its name still binds us all together.”[3]

Composita Ocgenta Sex,is the story of a young woman named Composita who has caught the attention of the Judges of Hades because of her unique composition. As the embodiment of “these many souls into one being” Composita must convince the Judges that she is pure and worthy to set out into the world; that the knowledge she gained and friendships she made at Smith will sustain her throughout her lifetime. In the Hall of Justice in Hades, Composita successfully deflects questions from the Judges of the Lower World,. At a reception for her held by her patron Persephone, a series of philosophers, poets, political and religious leaders move through the Hall of Justice where Composita continues to display her knowledge. She holds her own with Euclid, Sappho, and Plato, until the men of science, Isaac Newton and Baron Leibnitz, both interested in optics and refraction, come to visit her. They seize upon her with an intense interest and dare her to allow them to refract her back into her “forty-nine elements.” If her soul is pure, they argue, there is not the slightest danger to putting her back ‘together’ again. Newton is successful in refracting Composita with a prism, and shows the Judges her 49 elements. But when she is brought back together again, she is not the same. A small flaw in her character, that of the sin of ‘cramming’ has turned her into a statue, much like Lot’s wife.

Composita the play is important because it is her debut to all faculty, family members and friends attending the Commencement performance. Prior to this performance, Composita was known only to a limited number of individuals: the members of the Class of 1886, the photographers Hardie & Lovell, and to John Tappan Stoddard. This was the first public affirmation of the identity of the Class, and how the bonds they formed at Smith would last a lifetime. Throughout the play Composita recognizes that she is the composite of a collective identity when she comments: “there is no stability about this compound,” (pg 13); and “By what axiom can I prove my whole equal to the sum of all my parts?” (pg20). In a scene taking place in a college classroom, she relates a series of collective memories provided by all the members of the Class of 1886 ranging from regional dances like the Virginia Reel, to readings of philosophy, Latin, and science from her four years. She experiences the exhilaration of joy, and the confusion of self-doubt. She realizes that she is indeed the sum of all parts of the class. When she runs into trouble she calls upon the collective, “Oh dear, my equilibrium is almost gone, but we’ll [italics mine] rally…” (pg 17). The play is a tour de force representing the education that the members of the class experienced at Smith. As Composita remarks to Homer, who has been sent by Persephone to bring Composita down to Hades, “I am the product of the higher education of women.” (pg17). The play also acts as reminder of the memories of their four years together.

Two other examples in the Class of 1886 records show how Composita and her photographic visage pervades the language of the Senior Class. The published version of their Commencement activities contains a Class Toast and the Class Statistics. The toast is titled, “The Class of ’86 Composita” and was written by Mary Eastman, who also happened to play Composita in the performance. The toast throughout comments on Composita, but stanzas 4-8 are particularly eloquent proof of her influence over the members of the Class of 1886,

-4-

“But who has before heard of bits that were human,

Being clustered together and forming a woman,

Producing results that quite silenced the critics,

And raised the demands for Dramatic’s fine tickets.

-5-

We give her our best, we give her our worst,

The last gives no more and no less than the first.

We give her expression and feature and tone,

A bit of ourselves–and we feel her our own.

-6-

“In Union is strength,” is a saying that’s trite,

And yet the ethical principle’s right.

We’ve proved it with four year’s experience dear,

Should Composita shake now, Ah wont it be queer!

-7-

Then bound firm together we’ll buffet the storm,

We’ll laugh at all weather, be it cold, be it warm,

Let it rain, let it shine, we’ll sink or we’ll swim,

But we’ll hold fast together, heart to heart, limb to limb.

-8-

The years of our quiet College life are now numbered.

The lessons are over, the bond must be sundered,

Composita is scattered with rustle and whirl,

And yet where’er flying, we parts of our girl.”[4]

In addition to the toast, these words from the Class Statistics also confirm Composita as the vessel by which the Class of 1886 will forever be known. “We are said to have a passion for detail. That passion has been gratified. The negatives (and positives) have been in turn exposed to the sensitive plate which now portrays the character of ’86. Here is a nature so complex, its phases baffle even while they charm. Fleeting expressions therefore must be lost. Her features alone are here. The sublter charm of varying emotions all you who know her must supply.” (pg 53).[5] The class statistician then describes the class’s wide-ranging attributes. Composita is embraced as the desire not to be separated from college life or one another.

Throughout their advancing years, members of the Class of 1886 kept in touch with one another through annually published Class Letters. This series of Class Letters, dating between 1887 and1948, provides a wealth of information about their post-Smith lives, but also provides us with an indication of their own sense of being a part of the Smith community. Composita is often mentioned in individual entries, such as this one from Bertha A. Chase in 1887: “It is with the anticipation of great pleasure that the communications of the forty-eight are expected by the forty-ninth of Composita Octogenta Sex.”[6] Composita appears in reunion meeting minutes, as well as in the July 1921 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly where a report of the Alumnae Assembly, a post Commencement activity, includes this description: “Anna Russell (Marble) represented the Class of 1886 and announced with Composita at her side [italics mine] that the Class had achieved their 100% participation in the AlumnaeFund, and were donating an additional $500 in commemoration of their reunion with which the purchase of 150 books of medieval Latin writers, ‘for Composita was devoted to Latin’ known as Migne’s Pathrologia Latina would be made.'”[7] So, as they celebrated their 35 year reunion, Composita still resonated strongly with the members of the Class. Composita appears in images of the Class through their 45th anniversary in 1931. At this reunion the Class read a poem to the newly graduated Class of 1931. It read:

“When we were in college and about your age

Composite photography was all the rage;

So we had our pictures ‘took’

You can see how we look,

Don’t you think we were “pretty and sage”?

Long after their graduation, Composita and photography played a major role in their lives, one that they wished to pass on to newly graduated Smith women.

Conclusion

The history of Composita as a visual desire of class identity and friendship is strongly linked with the interests of a single professor at Smith College, the philosophy of education and residential system at Smith College, the self-governance of the Class of 1886, and with issues of heredity and race at large. We have seen Composita and photographic language pervade the photograph albums and printed words of the Class of 1886. By all of their actions, over the four years at Smith, the Class of ’86 strengthened their identity within the confines of academic rigors and residential regulations. For some, it would be the first and only time they could control their own destinies, so these four years had further special meaning. It is certain that inter-class rivalry fostered many of the decisions the Class made concerning their identity, whether deciding about the color of a class sash, or designs of a class pin or stationary. In the creation of Composita, the act of sitting for a photograph expanded from individual to group conceit. That the Class of ’86 wanted to share their post-Smith life with Composita, by returning her to reunions, is another indication that Composita was a true reflection of the Class. By taking their composite photograph and imbuing that image with a collective personality, by keeping Composita “alive,” the memories of the Class remained viable and their experiences at Smith validated.

Perhaps an equally interesting testimony to the influence of Composita and the Class of ’86 is that they spawned a minor tradition of other classes taking their own composite portraits. The College Archives has composite photographs for the Classes 1887, 1889, 1890-1892. While it does not appear these classes has the same intense relationship to their photograph that the Class of ’86 had, it is interesting to note that these ‘daughters of Composita’ were made at all.

Composita and the Class of ’86 remain forever linked, and her meaning is as individualistic as it is collective. Or in her words, “Such fortune never came into my wildest earthly dream!”

[1] Annual Circvlars 1883, p 14.

[2] Class of 1886 Meeting Minutes, October 23, 1885

[3] Smith Alumnae Quarterly, no.4, August 1934, p 439

[4] Class of 1886 Toast, in Smith College Commencement Exercises 1886

[5] Class Statistics, Class of 1886 in Smith College Commencement Exercises.

[6] Bertha Chas class letter 1887,pg 7.

[7] Smith Alumnae Quarterly, July 1921